The US housing market is chronically undersupplied. This is a direct result of a long-term, secular trend that began after the 2008/2009 Global Financial Crisis (the “GFC”) and has worsened each subsequent year. Prior to the GFC’s end, the US had a peak estimated housing surplus of 2.9 million units. However, after the GFC ended and its effects on the residential construction sector became fixed within the economy, this surplus declined every year until housing demand surpassed supply in 2017, when a shortfall of 731,000 units materialized, according to Kingbird analysis of Federal Reserve Board of St. Louis, US Census Bureau, ACS IPUMS, and CoStar data. This shortfall has since grown to between 3.8 and 6.8 million, as of 2020, according to Freddie Mac Housing Supply: A Growing Deficit May 2021 and National Association of Realtors Housing is Critical Infrastructure: Social and Economic Benefits of Building More Housing June 2021.

While the economic slowdown following the GFC was the immediate cause of this housing shortfall, it was ultimately worsened and secularized by three trends: 1) the implementation and intensification of zoning, land-use, and environmental regulations; 2) rising construction input costs, particularly land prices; and 3) consistent labor shortages. While construction input prices and labor supplies do go through cyclical fluctuations, the long-term, secular trend exhibited by these two factors has accelerated the housing shortage.

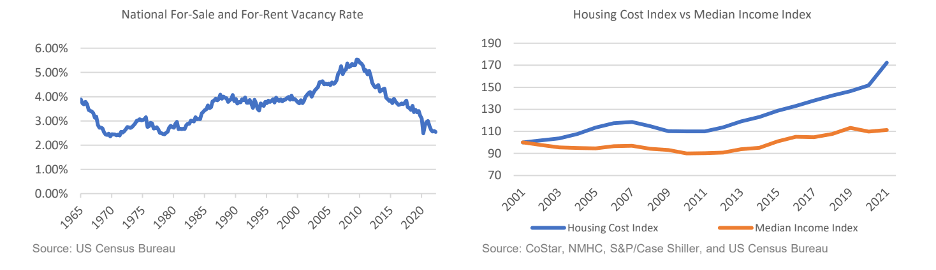

These trends have resulted in historically low vacancy rates and rapid rent and home price growth, relative to incomes, across the nation, as exhibited below.

While the housing supply shortfall is evident throughout the housing market, it has been most acute for the workforce renter segment, defined as renter households earning between $45,000 and $75,000 annually. This cohort is the largest renter segment, at 23.6% of renter households, yet the supply of existing and new high-quality, affordable rental housing available to them is constricted. As a result, the workforce rental vacancy rate is lower than the overall market and, consequently, rents in this sector grew at a faster pace than the market average.

This dynamic has rendered the workforce rental housing sector an ideal target for capital allocation within a well-diversified portfolio, as it improves cash distributions and enhances capital values for investors. Historically, investing in this high demand/low supply segment has yielded superior returns relative to other housing segments. Workforce housing focused funds returned an average net IRR of 16.4% between 2009 to 2019, whereas high-end housing funds yielded an average of 10.7%, according to Kingbird Analysis of Preqin Data.