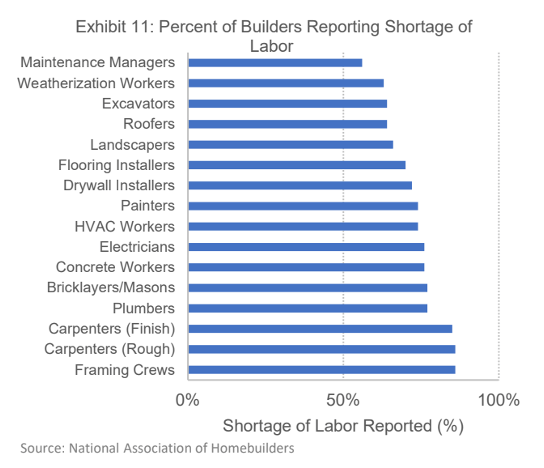

Residential construction employment has yet to recover from the Global Financial Crisis. Employment in the sector peaked at 1 million workers in 2006, then troughed at 528,000 in 2011. Only 921,700 were employed in the industry as of August 2022 – a similar employment level to July 2004, according to Kingbird Analysis of Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Data. As a result, an estimated 70% of construction firms have difficulty finding qualified employees, per Exhibit 11.

This labor shortage is a result of multiple long-term trends in the US that were exacerbated by the 2008/2009 Global Financial Crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020/2021. Many skilled construction workers, which are hard to replace, have recently or will soon enter retirement, with an estimated 22.7% of them aged 55 years or older, according to Kingbird Analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics Data.

This labor shortage is a result of multiple long-term trends in the US that were exacerbated by the 2008/2009 Global Financial Crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020/2021. Many skilled construction workers, which are hard to replace, have recently or will soon enter retirement, with an estimated 22.7% of them aged 55 years or older, according to Kingbird Analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics Data.

Despite this, there is a limited pipeline of young people with the skills necessary to replace these retirees. This is a result of the de-prioritization of vocational training programs in the American education system. Public schools typically eliminate vocational programs when faced with budgetary issues. In addition, public schools put an emphasis on college attainment and white-collar employment over skilled trades. As a result, the share of US high school students enrolled in career and technical education programs has declined from 20.0% in 2009 to 18.7% in 2020, according to Kingbird Analysis of US Census Bureau and Perkins State Plans and Data Explorer Data.

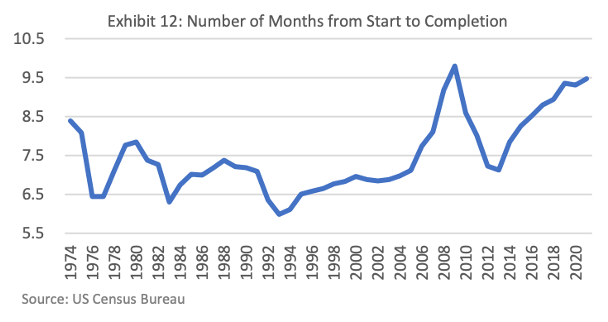

Slow productivity growth is another structural factor that impedes new supply in the housing sector. Construction sector labor productivity has been essentially flat, growing at an average annual pace of just 0.6% from 2011 to 2020. In contrast, overall private nonfarm labor productivity grew at an average rate of 1.1% per year, according to Kingbird Analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics Data.

Fewer, less productive laborers mean less efficient labor supply which, in turn, hampers overall construction. This is best exemplified by the increase in the average length of time it takes for a housing unit to complete, which grew from 8.4 months in 1974 to 9.5 months in 2021, as displayed in Exhibit 12, according to Kingbird Analysis of US Census Bureau Data.